Thurs, Nov. 3 at 7:30pm; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts; 701 Mission Street in San Francisco

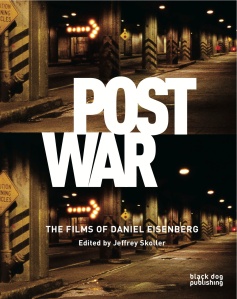

Tonight’s screening celebrates the publication of POSTWAR: The Films of Daniel Eisenberg, published by Black Dog Publishing and edited by Jeffrey Skoller. This screening will feature Eisenberg’s 1997 film Persistence, which combines footage of a circa-1946 war-devastated Berlin shot both by U. S. Army cameramen and Roberto Rossellini in the creation of his Germany Year Zero, with Eisenberg’s own documentation of that city in the early 1990s.

Daniel Eisenberg and Jeffrey Skoller in person

more info here / advance tickets here

from the introduction to POSTWAR: The Films of Daniel Eisenberg by Jeffrey Skoller:

The cinema of Daniel Eisenberg makes the present waiver. His films reverberate across time, bringing the events of the past into a present constituted by constant flux. In his work, Eisenberg is preoccupied with the ways past events continue to accrue new meanings and power as they move through time, across cities, continents, political and personal geographies. These rigorously formal films are timepieces that are at once documents of the dynamic present, and an interrogation of the meanings produced from the materials our culture uses to connect to the flow of time.

POSTWAR: The films of Daniel Eisenberg is the first major critical study of this unique American filmmaker who began making films in the late 1970s. Rather than a mid-career survey, this volume focuses on Eisenberg’s four thematically connected films, made between 1981 and 2003, which when taken together, trace the on-going implications of the events of the Second World War and the fall of the Berlin Wall—the structuring political events of the second half of the twentieth century— and continue into the twenty-first. Refusing to join in the popular claims of the “end of history” that has characterized the rhetorics of closure and a break with the past of the Cold War period in the midst of geo-political restructuring and economic globalization, Eisenberg instead explores the ways these events continue to unfold as structuring elements of the personal and political present. As works of visual history, the films engage contemporary questions about the nature of time—relationships between past, present and the future—the transformation of the meanings of events over time and the problems of representing those elements of past events that defy coherent narrativization.

…Persistence: Film in 24 absences/presences/prospects, (1997), is a portrait of the city of Berlin shot during the period of unification in 1991. In its transition, the city’s modern history is revealed as a nodal point for much of twentieth century Europe’s calamitous transitions, and is perhaps Eisenberg’s most complex film. Persistence is an episodic work that turns the city into a kind of time machine as it moves back and forth between different historical moments and the events that constitute them. The film itself becomes a document of the city in the process of transformation, suspended between the demolition of a divided city, a signifier of Germany’s total defeat in the Second World War and its renovation as the capital of the newly unified Germany. There are two essays that approach this third film in very different ways. In the first I invited Leora Auslander, an historian of European social history whose research focuses on the material culture in France and Germany, to write on the film as it relates to her own work on the twentieth century history of Berlin. In her essay, “Looking Across the Threshold: Persistence as Experiment in Time, Space, and Genre” she argues that in addition to being a work of cinematic art, Persistence is also a work of history. Her essay explores the ways that Eisenberg uses the film medium to expand the possibilities of historiography as a discipline. As Auslander writes, the film has much to teach historians about the specific problems it addresses—”evoking the contrast between the drama of historical cataclysm and the seeming normality of everyday life.” In her close and sensitive reading of the film, she shows how Persistence, through a kind of poetics of time, through the textures of its images and juxtaposition of its sounds, through various kinds of documents and texts, is able to reframe traditional historical narratives of chronological unfoldings with more complex narratives of multiplicity and simultaneity. Auslander explores the ways the film medium itself activates other experiences of history not usually considered to be traditional parts of the historian’s repertoire such as affects, sensations, and the dynamic experience of a world in flux. Like Eisenberg in Persistence, Auslander in her own research explores the absent presence of the once large Jewish community in Berlin. In the essay she skillfully integrates her own research on the material artifacts—photographs, documents and personal objects that surround the deportations of Berlin’s Jews during the war—with Eisenberg’s own visual explorations of the remnants of that community in the present. For Auslander, Persistence demonstrates that “attention to the situatedness of the historian and to the aesthetic and affective is not in contradiction with the historian’s mission of conveying as close as she can come to the truth of the past, while being useful to the present.”

The second essay on Persistence foregrounds German unification and the ways that historical break is made visible in the multiple forms of imagining the archive of German political and cultural history. In his essay, “The Persistence of the Archive: The Documentary Fictions of Daniel Eisenberg,” cultural and literary theorist Scott Durham thinks about the ways the archive is created, recreated, and appropriated in the construction of new narratives for the history of an uncertain present. Taking off from Michel Foucault’s remark that, in his excavations of the historical archive, he had never written anything but fictions, Durham begins with the film’s account of an emblematic shift in the German political and cultural landscape since unification: the opening up of the archives of the Ministry for State Security, the Stasi, to its former subjects of surveillance, as part of the preservation of Stasi headquarters as a museum. Durham uses this to explore the ways in which Berlin itself appears in the film as a vast archive of documents and monuments, in which successive or contending archival fictions coexist. In Persistence, Eisenberg documents the process through which a newly unified Berlin attempts to refashion itself by reframing and reordering the elements of both its Communist and Nazi past. Durham shows how remainders of this earlier strata of German history with their monuments to Lenin and ruined churches and synagogues can still be read within and alongside the new history as it is being rewritten, much in the same way that the discerning eye can detect the underwriting of a palimpsest. It is in this sense, as Durham writes, that Persistence becomes “an archive of archives, which at once constitutes a new archival space of its own and invites us to interrogate the relations between archival formations, and the narratives associated with them.”

—Jeffrey Skoller