All My Life (1966) by Bruce Baillie

CROSSROADS 2020 — program 1

Ever Westward: Remembering Bruce Baillie

program community partner: Canyon Cinema Foundation

On April 10, 2020, the world lost Bruce Baillie (b. 1931), the beatific filmmaker who, in 1961—with a simple outdoor film screening in the East Bay community of Canyon CA—birthed both San Francisco Cinematheque and Canyon Cinema.

Widely hailed as a master of 16mm filmmaking, Baillie’s works epitomize the “lyrical” mode of filmmaking strongly identified with ‘60s era northern California counterculture. As exemplified in such films as Valentin de Las Sierras, Baillie’s Bolex—almost always hand-held—functioned as a graceful extension of his body and eye, giving breath to the living world through impressionistic imagery and subtle, caressing motion. His editorial hand wove his striking imagery into lyrical flows of cascading visual poetry, as seen in To Parsifal (1963). Castro Street (1966)—a landscape study of a Richmond CA trainyard—is a 10-minute tour-de-force on 16mm superimposition achieved both “in-camera” and through laboratory printing. And to this day, the single-shot All My Life (also 1966)—a three-minute depiction of a northern California landscape; fence, flowers and sky—remains deeply inspiring in its profound simplicity.

This online screening is presented in tribute to this artist and presented digital translations of Baillie’s stunning work provided by Canyon Cinema. When Cinematheque’s theatrical screenings resume (as soon as is safe), we will present a selection of Baillie’s works—including his 1970 masterpiece Quick Billy—in their luminous 16mm glory.

Ever Westward, Eternal Rider…

Rest in Peace Bruce Baillie

SCREENING: Valentin De Las Sierras (1968); Roslyn Romance (Is It Really True?) (1974); Tung (1966); All My Life (1966); Castro Street (1966); To Parsifal (1963)

TRT: 61 minutes

Valentin De Las Sierras (1968) by Bruce Baillie

Song of revolutionary hero, Valentin, sung by Jose Santollo Nasido en Santa Cruz de la Soledad; Chapala, Jalisco, Mexico. (Bruce Baillie)

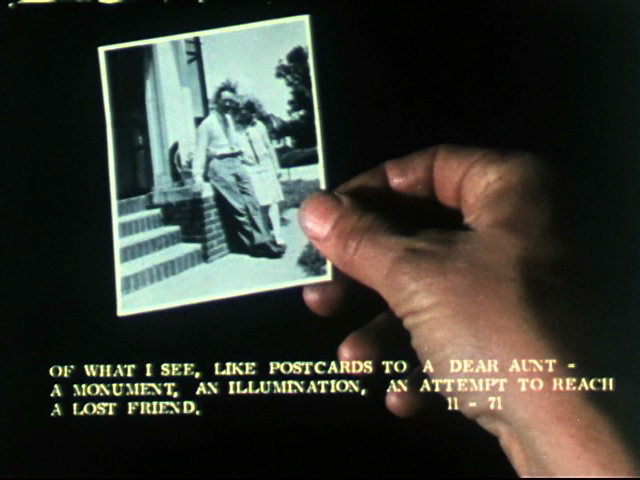

Roslyn Romance (Is It Really True?) (1974) by Bruce Baillie

When I was filming while living in the small Washington mountain town, Roslyn, I noticed it was to be a romance, in the sense of narrative, as well as a question: “Is it really true?” (i.e., what my neighbors held to be reality?) I began my inquiry in this locus, this film with a “postcard form”—I would share, mail, exhibit the reels of film during and after as if they were “correspondence with a dear friend…” The work seems to be a sort of manual, concerning all the stuff of the cycle of life, from the most detailed mundanery to … God knows. (Bruce Baillie)

Tung (1966) by Bruce Baillie

Tung is a portrait of a friend; sandy skin and flaxen hair in the early-morning light. (Bruce Baillie)

All My Life (1966) by Bruce Baillie

Caspar, California, old fence with red roses. (Bruce Baillie)

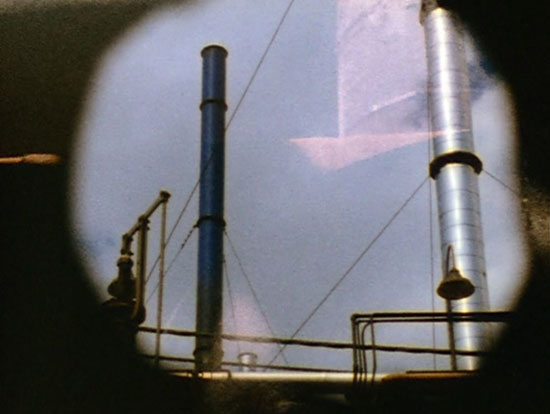

Castro Street (1966) by Bruce Baillie

Inspired by a lesson from Erik Satie; a film in the form of a street—Castro Street running by the Standard Oil Refinery in Richmond, California… switch engines in one side and refinery tanks, stacks and buildings on the other—the street and film, ending at a red lumber company. All visual and sound elements from the street, progressing from the beginning to the end of the street, one side is black and white (secondary), and one side is color—like male and female elements. The emergence of a long switch-engine shot (black and white solo) is to the filmmaker the essential of consciousness. (Bruce Baillie)

To Parsifal (1963) by Bruce Baillie

Using the European legend as basic structure, as well as the hero: “He who becomes slowly wise.” A tribute to summer. (Film-Maker’s Cooperative)

Born in South Dakota in 1931, Bruce Baillie served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War and studied filmmaking for a year at the London School of Film Technique. He moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s and within a few years became a guiding light of the New American Cinema. Simultaneous to his earliest personal experiments in 16mm, Baillie launched Canyon Cinema in the redwoods over Oakland in 1961. As he recounted to interviewer Scott MacDonald, “Immediately I realized that making films and showing films must go hand in hand, so I got a job at Safeway, took out a loan and bought a projector.”

Born in South Dakota in 1931, Bruce Baillie served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War and studied filmmaking for a year at the London School of Film Technique. He moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s and within a few years became a guiding light of the New American Cinema. Simultaneous to his earliest personal experiments in 16mm, Baillie launched Canyon Cinema in the redwoods over Oakland in 1961. As he recounted to interviewer Scott MacDonald, “Immediately I realized that making films and showing films must go hand in hand, so I got a job at Safeway, took out a loan and bought a projector.”

As Canyon fanned out across the Bay Area and developed into the cornerstone experimental film distribution cooperative it remains today, Baillie took to the road to collect material for a series of intensely lyrical works that helped to define “visionary film” in the 1960s. Early efforts like On Sundays and The Gymnasts gave an inkling of Baillie’s prevalent mix of documentary and fantasy, as well as his penchant for ripening superimpositions and exploration narratives. Canyon newsreels such as Mr. Hayashi (1963) proposed a concentrated form of cinema-as-haiku that Baillie would return to in later works like ALL My Life (1966) and Pieta (1998).

Baillie’s fully realized quest films (Mass For The Dakota Sioux (1964), Quixote (1965) and Quick Billy (1970) in particular) envelope laments for humankind’s destructive impulses in luminous formal surfaces. As much as his contemporary Stan Brakhage, Baillie developed a bold film language to convey visual phenomena outside the realm of dramatic realism. Baillie’s artisanal mastery of cinematographic layering, in particular, brings about immanent perceptions of the radiance and transience of all things. The lucidity of vision in his work is an end in itself, betraying an almost amorous desire for spiritual ballast.

In a simple ballad like Valentin De Las Sierras (1968), for instance, the intensity of proximate vision evokes a radical empathy with other beings. In Castro Street (1966), perhaps his most famous work, an industrial thoroughfare supplies Baillie’s Bolex camera with the raw materials for a matted tour de force of synaesthetic effects. Film scholar P. Adams Sitney wrote that Baillie’s “problematic study of the heroic” and “equivocal relationship to technology” served to complicate his resplendent lyrical forms, though one could just as easily say that the films he made during this period give poetic expression to the inner struggles of the 1960s. His epic Quick Billy grew out of a brush with mortality while living at a commune in Fort Bragg, California, and its expansive passages through interior illuminations, autobiographical reflections and Western pageantry make it a fitting capstone to a turbulent decade.(Max Goldberg; bio originally written for Fandor)