program online March 27–August 4, 2020

presented in partnership with McEvoy Foundation for the Arts

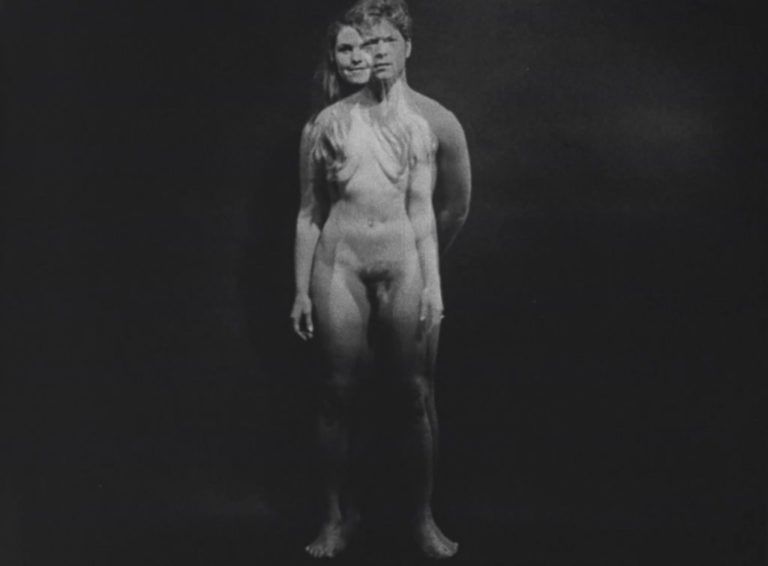

Pictured: Jean Luc Nancy (2018) by Antoinette Zwirchmayr

certainty is becoming our nemesis is guest curated by Steve Polta of San Francisco Cinematheque. The program is produced and was commissioned by McEvoy Foundation for the Arts in conjunction with Orlando, guest curated by Tilda Swinton and organized by Aperture, New York.

A note from the organizers: The world has become profoundly more uncertain due to the spread of COVID-19 since certainty is becoming our nemesis debuted at McEvoy Foundation for the Arts’ San Francisco gallery in early February 2020 alongside the exhibition Orlando. In light of the gallery’s temporary closure to combat the pandemic, San Francisco Cinematheque and McEvoy Arts have partnered to make the program available online in its entirety through August 5, 2020 in the hopes that the works of these extraordinary artists may provide comfort, inspiration, and even escapism to viewers worldwide during this very uncertain time. Cinematheque is proud to present this version of certainty is becoming our nemesis as its inaugural online exhibition.

August 5, 2020 UPDATE: The McEvoy Foundation for the Arts has re-opened for in-person gallery visits and will be screening certainty is becoming our nemesis on a continuous basis during gallery hours through September 5, 2020. Please see their website for more information about visiting.

certainty is becoming our nemesis

I’ve been thinking about how certainty is becoming our nemesis. How doubtlessness is killing our ability to expand as a society and as individuals. How the once essential search for a definable and immutable, identity has become stifling to our sense of development and the possibilities of finding true fellowship with other complex, variously wired, hesitant sensitive beings. (Tilda Swinton, “Orlando: Spirit of the Age,” Aperture, Summer 2019, #235)

If John Cage’s 1952 composition 4’33” and its landmark performance are seen as a refusal to commit or to perform, then it should be said that the piece also inaugurated an aesthetic of ambiguity and expressionlessness, one that has whispered like a queer phantom through Western art. Today, as the boundaries between self-expression and participatory surveillance—in both public settings as well as online platforms—are becoming increasingly blurred, ambiguity of identity has manifested for many as a crucial survival strategy and act of social and political defiance.

At the same time, as discourse on gender fluidity has become much more mainstream, it has extended into a rich and exciting new canon of contemporary artworks. The film and video works in certainty is becoming our nemesis illustrate this trend, foregrounding the expansive possibilities of personal invention and the assertion of self in radically new frameworks. Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, as well as Sally Potter’s 1992 film interpretation—with Tilda Swinton’s defiantly ambiguous portrayal of the title character—are deeply prescient to this moment in which certainty, as a principle, is in question.

Drawing inspiration from the resonant exhibition Orlando, certainty is becoming our nemesis presents works on themes of transformation, self-invention, gender performance and family—chosen and otherwise. While flirting with notions of timelessness and perpetuity, these works refute notions of stability and offer radical gestures of intimacy. (Steve Polta, January 2020)

Program Notes by Steve Polta

Special Thanks and recognition for support and inspiration for this program are extended to Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, the Canyon Cinema Foundation and the Luis De Jesus Gallery Los Angeles.

Riverbody (1970) by Alice Anne Parker

This continuous dissolve of eighty-seven male and female nudes announces a cinematic interest in ambiguity of identity that precedes twenty-first century discourses. Posed in a darkened non-space and accompanied by an amniotic soundtrack of gently lapping waves, the film’s subjects seemingly exist outside of time, in an ever-shifting state of migrating personality and gender. www.aliceanneparker.com

Special thanks to Canyon Cinema Foundation.

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Métamorphoses du Papillon (2013) by Pere Ginard

Recalling the works of Joseph Cornell, Pere Ginard’s films and collages explore early cinema, home movies and childhood. Concluding with a citation of French cinematic pioneer Gaston Velle’s 1904 film of the same name, Ginard’s darkly celebratory film presents an impressionist vision of rebirth and transformation. www.pereginard.com

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

The Queen of Material (2014) by Rajee Samarasinghe

The films of Rajee Samarasinghe elegantly synthesize portraiture, materiality and evocative meditations on family and Sri Lankan culture. This elusively brief work pays homage to filmmaker Kenneth Anger while envisioning a primordial world of sensual and regal adornment seemingly conjured by a mysterious dreamer. www.rajeesamarasinghe.com

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face (2012) by Zach Blas

Zach Blas’ works refract an activist’s vision through science fiction and a dystopian critique of twenty-first century culture. Facial Weaponization Suite scrutinizes racialized and gendered tendencies of contemporary surveillance infrastructure, while Fag Face posits how anti-surveillance technology might provide activists access to “a fog of queerness that refuses to be recognized.” www.zachblas.info

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Rote Linie (2015/2016) by Rosa John

An improvised and performative self-portrait, Rosa John’s Rote Linie confronts the viewer with an abstracted and symbolically defaced body. Simultaneously intimate and alienating, the subtly confrontational film makes a complex statement on introspection, interiority and, ultimately, the inscrutability of identity.

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Shape of a Surface (2017) by Nazli Dinçel

Nazli Dinçel uses her hand-held camera as an extension of eye and body to explore the Turkish ruins of Aphrodisias, using mirrors to both conceal and reveal a destabilized landscape. Echoing Viviane Sassen’s work in the exhibition, which explores expressions of power and sexuality inherent in relics of seventeenth century French royalty, Dinçel’s film juxtaposes human bodies with views of decaying statuary, evoking intimations of both eternity of form and the brevity of existence. www.nazlidincel.com

Unison (2013–2017) by Zackary Drucker

With its non-linear structure, Zackary Drucker’s dreamlike Unison imagines phases of an always evolving trans identity existing simultaneously over an idyllic afternoon. A similarly complex examination of gender and sexuality is seen in Drucker’s 2019 series Rosalyne (on view in the exhibition). Both works illustrate the artist’s ongoing documentation of transgender legacies, relationships and experiences through portraiture and collaboration. www.zackarydrucker.com

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Jean Luc Nancy (2018) by Antoinette Zwirchmayr

This foreboding, science fiction vignette contemplates philosopher Jean Luc Nancy’s ruminations on community, individuality and alienation. In an oblique interior narrative, an individual considers her relationship to the group, weighing considerations of security and community against the imperatives of following one’s own path. www.antoinettezwirchmayr.com

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Between Dog and Wolf (2018) by Julia Dogra-Brazell

With sparse, elemental imagery and a multivalent narrative voice collaged from texts by Virginia Woolf and filmmaker Raul Ruiz, Between Dog and Wolf considers liminal states of transition and uncertainty. In a disruptive assertion of autonomy, an aloof figure regards the viewer before returning to a state of defiant disengagement. www.juliadograbrazell.com

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

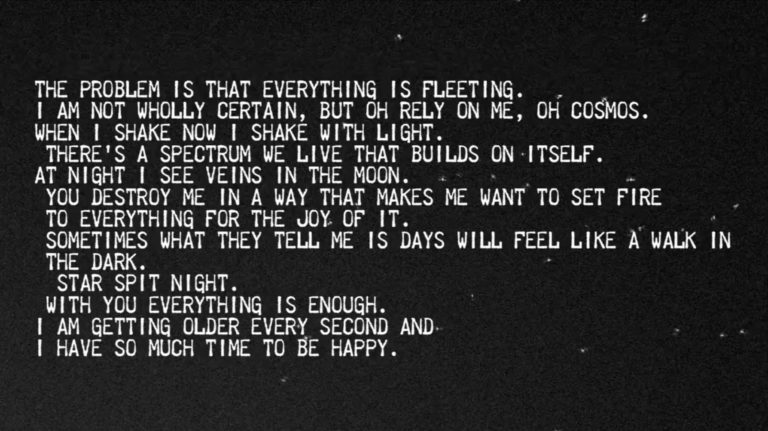

the problem is that everything is fleeting (2015) by Karly Stark

A visual poem of expansive, annihilating love. With a hesitant yet ardently passionate voice, Karly Stark’s brief film suggests eternity of being and infinity of self. www.karlystark.com

FILMMAKER Q&A HERE

Q&A with Alice Anne Parker

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

It seems irrelevant, but I’m thinking about all the old filmmaker friends of mine who are dead—Yikes! Bob Nelson, Scott and Freude Bartlett, John Knoop, Peter Hutton, the lurid and wonderful George Kuchar [and his equally wonderful brother Mike, still with us]—and what a great time we had making movies! I was an academic, working on my doctorate at UC Berkeley when I started teaching English at SFAI. Goodbye PhD. What could be more fun than making movies with these witty, brilliant pals?

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

I think I was interested in seeing a lot of people nude when I made Riverbody. Maybe it had something to do with being undefended. Exposed. Years later I became a professional psychic, which I suppose means being undefended in a completely different way. Being a psychic, for me anyway, involves poking around in someone’s consciousness. Someone has a problem and they need help. You go into them and do a little reorganizing until the problem dissolves—but of course, you are undefended and exposed as well. I didn’t ever think of myself as an artist. But maybe that’s how art works. It can change your awareness of something in a seemingly effortless way. Later I wrote a few books, one still in print after thirty years.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

My only connection is that I’ve known Tilda for some years.

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

I didn’t ever consider themes or my artistic process. I made movies of things I wanted to see. The result appears to be much of the above, certainly transformation and ambiguity of identity… I’m not so sure about survival strategy or defiance.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

It has certainly made me very happy! That is, I’m delighted that my movies are still being shown. So looking forward to watching the entire program.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

My husband and myself are old, both in our eighties. We’re not terrifically concerned about our own survival, but we also have kids and grand-kids. We speculate that this mess may be the forerunner of a brave new world, more conscious, less opportunistic—there seems to be some evidence for this. My husband is a novelist and a painter, I’m enjoying myself doing very little.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

Probably Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala [1975]—I’ve seen it so many times, but it always moves me.

Q&A with Pere Ginard

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

I am an illustrator and filmmaker based in Barcelona (Spain), which is where I am confined while answering these questions. And I think I can describe myself much better by listing my three eternal artistic references: filmmakers Jan Svankmajer and Stan Brakhage, and author/illustrator Edward Gorey. Even COVID-19 has not changed that.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

It’s an important film in my career. I usually get a lot of inspiration from literature when making a film and I like to make versions of novels or stories, reinterpretations, etc. but in this one I went a little further: I directly vampirized a silent film and slowed it down and imagined very slow-motion metamorphosis would be like… like the digestion of a snake. And then there is sound design: this one of the first films in which I begin to take the narrative potential of sound very seriously, so much so that in this film, sound is often more present than image.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

I read Virginia Woolf’s novel many years ago, for me it is her most interesting work (I will never forget how she narrates the transition from the 18th to the 19th century). I saw the Sally Potter film much later and I must admit that I remembered very little: I took advantage of being part of this project to review the film.

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

Subjects such as transformation, reinvention, uncertainty, doubles (and by extension the sinister and the weird) are subjects that undoubtedly are part of my interests and obsessions, but always from a much more phantasmagorical point of view. Let’s say that my approach to all these themes is much more poetic than social.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

Within the context of the program and the exhibition, suddenly my film seems to me much more linked to a current social issue than ever. It is strange and at the same time nice to see how the perception changes.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

After the first days of confusion and daze, I have become accustomed to a new routine—much calmer, quieter and more intimate—that I am really enjoying. The projects that come out, even without intending to, reflect this reflective state and focus on the small: series of tiny drawings, small animations of microscopic beings. I suppose that, unconsciously, this recent work is influenced by the constant medical news that we are all consuming these months.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

David Toop’s essays, and especially his book Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener (2010). His reflections on music, sound and literature are fascinating. Packed with cultural references of all kinds, Toop’s essays contain a thousand books in one.

Q&A with Rajee Samarasinghe

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

My name is Rajee Samarasinghe, writing from California. I am a filmmaker currently working on a feature documentary called Your Touch Makes Others Invisible which examines tortured interactions between the Tamils and the Sinhalese in the aftermath of the Sri Lankan Civil War. I also have a new short film called The Eyes of Summer which was released earlier this year and has to do with my mother’s interactions with spirits during her childhood.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

The Queen of Material is one of my earliest films and I see traces of it in a lot of my subsequent work. It demonstrates, in it’s very brief runtime, a lot of my curiosities as a filmmaker in terms of hybrid forms and exploring certain aspects of Sri Lankan culture.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

I have no prior relationship to the book nor the film adaptation, though I like the idea of exploring these works after the fact especially (perhaps unfairly) in relation to my own piece. I am, of course, familiar with those artists and have tremendous admiration for their work—I’ve been a Tilda Swinton fan forever!

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

These concepts certainly do speak to The Queen of Material and some of my other work like everyday star, for example. Often my works reveal themselves to me later in the process of creation, so these are themes I obviously care about innately and that pop up constantly throughout the things I make.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

I think it’s unavoidable to not see my film through the scope of this program or any other program it’s in. The Queen of Material remains an inherently mysterious piece to me. I made it with the intention of not knowing too much about it. I started with the idea of creating a world using what I felt were the primary rhetorical devices in cinema: the portrait and the landscape—though in making landscapes out of saris that also reflected inward. So, over the years, works around the piece have certainly clued me into its inherent mystery but it still remains elusive and perhaps these clues are better left unsaid.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

I just feel extremely lucky to have the basic things I need to survive like food and shelter. I should be editing a new short film of mine but I haven’t felt the urge. I’ve been more engaged with other people’s art and simply reflecting on my own practice. Though I hope to get back into it sooner than later.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

Very recently, This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection by Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese and films and writing by Kathleen Collins. Quarantine honorable mentions to Moving On by Yoon Dan-bi, Prisoners by Denis Villeneuve and The Strange Case of Angelica by Manoel de Oliveira.

Q&A with Zach Blas

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

I am an artist living in London, originally from the US, and I’m currently on lockdown in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. These days, I am making work on the fantasies and beliefs swirling around artificial intelligence.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

I have a long-standing interest in the cultures and politics around digital technologies. With Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face, I started to question how biometric facial recognition standardizes and reduces the complexities of the face to a calculable identity. How very un-queer! Now that facial recognition and AI are so entwined, I feel that I’m on a quite clear path that can easily be traced back to this work, which was made about 8 or 9 years ago.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

I came to Tilda Swinton through the films of Derek Jarman when I was a teenager. Her performance in The Last of England (1987) has particularly stayed with me over the years. I’ve always wanted to work with Tilda. I even tried to get in touch with her to consider producing my 2018 film Contra-Internet: Jubilee 2033, which is a re-imagining of Jarman’s 1978 film Jubilee.

[NOTE: Zach Blas’ Contra-Internet: Jubilee 2033 is featured in Cinematheque’s online program, I Hate the Internet: Techno-Dystopian Malaise and Visions of Rebellion, online now through May 16.]

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

I think of my work as conceptual queer science-fiction. I am interested and motivated by transformation into the unknown, the alien, the opaque. I’m not so interested in queer as an identity category. I do not think of my anti-biometric masks—like the Fag Face Mask—as simply hiding, disappearing or enacting a kind of individual privacy. I think of the masks as demanding a collective opacity through a gesture that I describe as informatically queer.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

My work is rarely included in queer exhibitions but rather exhibitions concerned with digital technology, so thanks for making room.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

I’m washing my hands constantly and not going out much, like many others. For the time being, I’m focusing my energies on two books I’m writing–one is a collection of my essays and the other is an edited anthology on Donna Haraway’s concept “informatics of domination.” I’m also in the research phase of a new installation that focuses on AI and religion. In part, this work is a re-imagining of Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

Lyra Pramuk’s new album Fountain, particularly the track “New Moon.”

Q&A with Rosa John

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

I am a visual artist and filmmaker with a background in media studies, and I am based in Vienna, Austria. In my work I like to follow multiple paths, thematically and methodically. But my main project of the past few years has been a series of works concerning the idiosyncrasy of the camera. I’m interested in how the material and the visual co-depend. I am currently doing some interdisciplinary work on the materiality of the camera and the use of metaphoric language to grasp the logic of a camera. I am also working on finalizing my PhD project in which I am pursuing a media archaeological approach to the history of the camera. Specifically, I am investigating the history of the company Paillard Bolex and the Bolex H-16 camera and its implications on visual culture, particularly artists’ film.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

The film Rote Linie (Red Line) incorporates elements like a performative and self-empowering way of filmmaking, the depiction of fragments of the human body, monothematic reduction and perhaps also the visual balance of recognizable specifics and abstraction which are characteristic of my work. But it was not conceived as a conceptual addition to my body of work, it’s one in a variety of approaches or paths (as put above). Likewise it’s not part of the previously mentioned project on the camera, but it does make use of camera-specific potentials. The film was shot on Super8, but I also work with 16mm or occasionally video. I love Super8, working with it is so flexible and playful and it opens up possibilities of very spontaneous filmmaking while still being film: a strip with tiny images on it. It is also a very simple film in the way that I worked with very basic means and by myself. I like to give myself that challenge to build something with minimal elements, things or people that are more or less already around.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

I’ve encountered these artists and their work (particularly regarding Orlando) many years ago as an adolescent or young adult, and have been intrigued by all of them—but I never yet engaged with their body of work profoundly, like really delved into it, as I would definitely like to. All the more so I was very happy that you as a programmer saw a connection. Such incidents assure me to keep going even if one sometimes doesn’t know where a path leads to.

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

I think ambiguity is the only valid definition of existence or identity. Every other sort of definition of the human identity just feels like cutting off air to breathe. Acceptance of ambiguity is just so liberating in so many regards of life. That’s my personal opinion or feeling or experience, and as such it probably plays into my work while not being explicitly about it. Just as I am a political person but don’t consider my work to be political art, or wouldn’t even insist to call it art, while I just want to make films, photographs, objects, arguments as a means of communication.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

To make a film or any work of art implies a lot of decisions and thoughts, some more explicable than others. In that regard I often argue with myself while I also think it is important for me to trust something beyond knowledge or understanding. A film or any work of art can and should open up different layers in different contexts. So I definitely reacted to the idea of body norms and transformation when making the film, but it came from a very personal place and the inclusion in the program shows me that it speaks to a larger frame of discourse. Also the gender aspect is intrinsic to the work, it’s not a coincidence that I used a lipliner for the body marking rather than any other sort of pen. But when I made that film I wasn’t even sure if I was ever going to show it to anybody. So I guess the inclusion in this particular program and exhibition also supports that approach of sharing. We might not be that different in our doubts and wishes after all.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

In the last weeks I’ve really felt a whole range of different sentiments, and then again there was not much time to give into these feelings as I am at home with a toddler and a preschool-aged kid during this lockdown, and they keep me occupied with the most ordinary things. And while my partner and I are splitting our efforts, it’s difficult to manage everyday tasks and also get work done. So far, I don’t think the current situation is impacting my personal approach to art making, but it further challenges the circumstances that allow me to find the resources to make art. I do find comfort in a sort of general slow down and the questioning of values that is taking place, although I’m afraid it won’t have a lasting effect.

Besides that, experiencing art is a very sensual thing for me, and while all those current efforts in the digital realm are great, the situation only nourishes my need for haptic, site-specific, “odorant” encounters with art.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

I had several wonderful and informative experiences of art in the last few months (like retrospectives of Margaret Tait at the Austrian Filmmuseum, Maria Lassnig at Albertina, Constantin Brancusi at Bozar in Brussels). The most profound (and still ongoing) impact on me has come from the broad cultural discourse on climate change and ecological matters, which had developed so intently before the current public health crisis. It should prompt us to reevaluate ways of doing things that we have gotten so used to, to reevaluate what to wish for – and this concerns the art world just as much as everyone else.

photo credit: Danielle Levitt

Q&A with Zackary Drucker

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

I am safe and secure at home in Los Angeles and very grateful for the many blessings in my life. It’s Earth Day [April 22, 2020], my dad’s birthday, and the kind of beautiful spring day that Los Angeles is famous for. There are carnations and poppies blooming in my garden, and pomegranate blossoms on the trees. For years I’ve been bouncing around, feeling like I’m maintaining a home that I don’t spend any time in, and now I’ve only got time at home. I’m working full-time (remotely) on a television project. I’m also writing a text for a performance and creating photographs at home.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

Unison is the last film I made with Flawless Sabrina, which also includes many of my biological and chosen family. Different phases of it were filmed over several years. The film explores traveling through time to witness one’s lineage, speaking to our predecessors and successors, and pondering what it means for a lineage to end with a gender non-conforming body.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

I’m a huge fan of Tilda Swinton starting from the moment that I saw Orlando when it was released on video in 1993 or 1994. As a young person in Syracuse NY, the media that I was able to find at the local independent video store and library were a lifeline, and Orlando was one of the first trans characters I recall seeing. It was so magical to see a boy character inexplicably become a woman overnight (if it were only that easy). It inspired my imagination and informed who I am today.

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

Yes, I’m always looking for survival strategies from elders. I hope to live a long life. We should be so lucky. I think that trans people’s mere existence is a multiplicitous form of defiance everyday, even in isolation.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

Tilda Swinton, Aperture did an incredible job with Orlando—the Aperture edition and the exhibition. I’m thrilled that the exhibition has had a sustained life online where people can witness their brilliance.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

I think the current health crisis deepens my commitment to human values. I think that it may change much of human behavior. There’s really no space for self-indulgence or narcissism in this time, and those are the values that our culture has been predicated on for many years. Working within limitations can be a tremendous gift, and this is one of those times when artists who are really committed to shifting our consciousness and shattering our social mores will shine. A lot of the bullshit will fall away. Few people will have time for petty, decorative or otherwise superfluous art.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

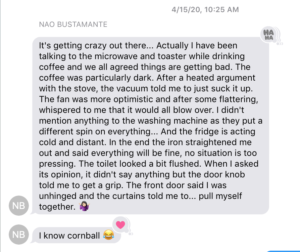

This text message from Nao Bustamante on a neighborhood group thread today:

Q&A with Antoinette Zwirchmayr

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

I have been isolated for about five weeks in the country, in a wine region in Austria, from which I can constantly observe Spring developing. My family has a house here, which we have been renovating for eleven years and is still far from finished. It is a versatile place. We have an outdoor kitchen, weeping willows and a fireplace. There is always something to do here. In the last few weeks I had the idea to write a script just for this house: the house as a starting point for a story.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

Jean Luc Nancy was my first commissioned work. An Austrian museum and a festival gave me a complex two-page concept for an exhibition, some money and very little time. I was kind of irritated by this approach, and in the end they didn’t even integrate the film into the exhibition. I was under a lot of pressure and I started thinking about the outside all the time. The question “will they like the film?” was always floating in the room. This thought is deadly for the artistic process. You should always think the opposite: “Let’s hope they don’t like it!” Unfortunately, we all become so accommodating, we all want our work to be loved. But to return to the film, I have to say that I have become very fond of it. And I would never have made it, if the circumstances hadn’t been the way they were. So, in hindsight, I am grateful for everything.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

The invitation to this program was special in the sense that I have been working for several years with the writer Angelika Reitzer on a script for a feature film called I am my hideaway. We wrote the screenplay for Tilda Swinton from the very beginning. Of course, we know that she will never play the role, but she helps us imagine the main character. It is a feature film script for a sci-fi movie. It’s very uncertain if this film will ever be realized.

There is another temporal connection to the exhibition. A few months ago, the FIRST full-length work by a female composer was performed at the Vienna State Opera. The piece was Orlando. I was very disappointed that I could not see it. There were conspicuously few performances, and the tickets were expensive. It was a great spectacle and there was an exceptionally large media response. The conservative opera audience reacted with outrage, of course. The fact that it took so long for a woman to get such a commission is revealing—it shows, once again, how far we are from an equal society.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

The current situation is particularly challenging for all of us. Nevertheless, as an artist one is equipped with certain survival strategies. Life as an artist is so uncertain and unstable. Every day, every year is different. You always have to keep busy and drive yourself, because nobody else does. You’re never used to a lot of money or other conveniences and in times like these, that can be an advantage.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

Probably the most impressive pieces I saw last year were Bakchen, a theatre play directed by Ulrich Rasche and two dance pieces by choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. And there was a performance by Meg Stuart. Terrific! These are rare moments when you are in the theatre and wish it should never end.

This crisis has shown me personally very clearly how important art is. I go to the theatre and cinema a lot. Often, I just took it for granted.

photo credit: Goso Tominaga

Q&A with Julia Dogra-Brazell

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

For the last twenty years, I’ve experimented with narrative

structure through film and video. Having moved to the south coast of England from London a few years ago, I answer you from there, close to the waves and sand you see depicted in the film. Transformed by the pandemic, it has become a siren landscape in which, we are told, no one should land and no one should linger.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

Between Dog and Wolf is the first of a trilogy of longer works (including Past Perfect and Terra Incognita) started in 2018 for a show in London in 2021. Previous films have been fleeting (1–4 minutes in length) relying on the condensation of montage for effect. Though I once thought it impossible, for this trilogy I wanted to see if I could ‘scale up’ and slow down without losing any of the intensity or depth of the earlier works. Living by the sea has, in any case, altered the rhythm and pace of my editing. More things seem possible.

As you know, certainty is becoming our nemesis is inspired by McEvoy Arts’ exhibition Orlando, itself inspired by Virginia’s Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation starring Tilda Swinton. What, if any, is your prior relationship to the work of these artists?

I’ve always admired Woolf. The first book of hers I read was The Waves. I guess it was inevitable that I’d think of her again when making this film. She allows access to such provisional states of interiority. Finding a correct distance—whether making or receiving a work—seems vital to the exchange offered by such encounters. Coincidently in this regard, I first came across Tilda Swinton asleep in a glass box at the Serpentine Gallery (for Cornelia Parker’s The Maybe) in 1995. At a time when fewer people visited galleries, I found myself standing alone in the space—with Swinton potentially awake and aware of my presence or asleep and possibly even dreaming. It brought the whole question of distance to the fore quite literally.

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

Not consciously. The starting point for this particular piece was the stranger who brings something initially alien to a shore: whether, as in this case, the Romans, Vikings, St. Augustine, artists or, today, migrants attempting to make it to the UK in precarious boats. But when making, I have to let even that go. At some point the logic is in the edit, the subconscious. I never reference anything too specific in my work.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

Imaginative and sensitive curation of this kind helps me to see that bearing witness—a preoccupation of much art-making today—is possible even from a slight distance and from an acute angle. I often worry about that. The balance between sustained resonance and specificity is a tricky business.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

There are practical and financial issues right now, of course, but my biggest concern is what kind of world we will find ourselves in after this. We need to dream and think big, so we don’t go back to living unintelligently as a species.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

Two pieces that really stay with me are Ryan Gander’s Locked Room Scenario (2011) and Tino Sehgal’s This Success/Failure (2007). They both put you on the spot when it comes to a response. More recently, the brilliant IFC series Documentary Now. It’s a great way to survive lockdown.

Q&A with Karly Stark

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your current artistic concerns or projects? Where are you answering this Q&A from?

I am an experimental filmmaker and lecturer currently hunkered down in my apartment in Oakland CA. I lecture in the School of Cinema at San Francisco State and teach courses that mostly focus on experimental filmmaking/production and queer/trans film theory, and my creative practice focuses on essay and diary filmmaking. I’m also currently working to incorporate hand-drawn rotoscope animation into my film practice, so that’s been taking up a lot of my time recently.

How does your film in this program relate to your ongoing practice or body of work?

I made the problem is… as part of a larger collaborative project in an MFA class at San Francisco State back in 2015. The project was a filmic translation of a renga poem—a member of my cohort made a one-minute film then passed it along to the next person, who made a one-minute film commenting on that film, etc. I was chosen to make the tenth and final film, so it was tasked with encapsulating all that came before it. I’ve always gravitated towards poetry in my films—in essay or diary work I always include a poetic mode of address either through voiceover or text on screen. So, I wrote the problem is… as a way of drawing together the themes I saw at work in the piece as a whole, and for me it always makes sense to have it come from a single voice, to try to be intimate and universal at the same time.

The program explores themes of transformation, self-invention, and gender performance and suggests that ambiguity of identity can operate as an emotional survival strategy and act of defiance. Are these themes something you consider in your artistic process or as central to your work exhibited here?

These are definitely huge themes in my work, and of course in my artistic process in general. I’m a non-binary queer filmmaker who makes really personal, lyrical films. My early films have all been vehicles to explore my relationship with my gender and sexuality—my first queer sexual experiences, my position as the first openly queer member of my family, etc. I also feel that queerness, ambiguity, transness, in all its forms and intricacies, is such a core part of who I am that it’s the filter through which I see everything.

In what way has your inclusion in this program (or in conjunction with the larger Orlando exhibition) impacted your view of the work itself?

I feel so honored and humbled to see my work alongside artists that I’ve admired from afar for so long and whose work I find wildly inspirational, and also just so many queer artists. This film is probably the only thing I’ve made that doesn’t have an overtly queer voice, so it also feels really affirming to have it screen within a program and exhibition that facilitates that lens or reading. It’s a film I made five years ago, when I was in a very different place than I am now, so revisiting it in a context that centers my current positionality has opened up a kind of diaristic reflection for me.

How are you coping with the current public health crisis? How has it impacted your approach to art making?

I’m remarkably privileged in that I am healthy and have secure housing, a few months of employment, and the ability to stay home and wait this out. Honestly, the first week I spent a lot of time furiously animating to keep myself really busy, but as the weeks have gone by I’ve taken a step back and focused on slowing myself down. I’ve mostly been journaling more, playing guitar and making music.

Lastly, what’s the last piece of art, media, or culture that exerted a profound impact on you?

A few things: Waxahatchee’s Saint Cloud. Katie Crutchfield and Marlee Grace performing together on instagram live, especially in the first week of social distancing. Watching mutual aid at work.