Landscape for Fire (1972) by Anthony McCall

Wednesday, February 18, 2026, 7:00 pm

Do You See What I See?

Works by McCall, Frampton, Schneemann and Sharits

BAYFRONT THEATRE AT FORT MASON CENTER

2 Marina Boulevard, Building B, Third Floor

San Francisco, CA, 94123

Presented in association with Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture

Admission: Free-$60 – sliding scale

RSVP link here

On view until March 8, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture’s exhibition Anthony McCall: First Light presents three seminal works of cinematic sculpture by the pioneering British artist, three “solid light” works—including the canonical Line Describing a Cone (1973)—non-theatrical installation works that transformed the possibilities of cinema; challenge the boundaries between film, sculpture, drawing, and performance and invite viewers to step away from the screen and into the sculptural beams of projected light themselves.

In association with this ongoing presentation, Fort Mason Center and San Francisco Cinematheque present a one-night-only screening featuring a trio of diverse works which were inspirational to McCall’s life and practice during the period of conceiving and creating Line Describing a Cone, three works suggested by the artist (all to screen in 16mm): Carolee Schneemann’s Plumb Line (1972), described by Schneemann as ”a moving and powerful subjective chronicle of the breaking up of a love relationship… a devastating exorcism, as the viewer sees and hears the film approximate the interior memory of the experience;” Paul Sharits’ Ray Gun Virus (1966), a film of pure flickering color, “affirming projector, projection beam, screen, emulsion, film frame structure, etc.,” a film as much projected on the viewers nervous system as on the screen; and Nostalgia (Hapax Legomena I) (1971), Hollis Frampton’s poetic ode to motion and stillness, anticipation and memory. Program opens with McCall’s rarely screened early work Landscape for Fire (1972).

Admission Note: Issued free RSVPs are valid for entry, even if the event appears sold out online. Free RSVPs will be held until 15 minutes before the event begins, after which unclaimed spots may be released to a standby line. Paid tickets are held slightly longer but do not receive priority over previously issued free RSVPs.

SCREENING: Landscape for Fire (1972) by Anthony McCall; 16mm screened as digital video, color, sound, 7 minutes. Exhibition file from the maker. Ray Gun Virus (1966) by Paul Sharits; 16mm, color, sound, 14 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema. Plumb Line (1972) by Carolee Schneemann; 16mm, color, sound, 18 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema. Nostalgia (Hapax Legomena I) (1971) by Hollis Frampton; 16mm, b&w, sound, 38 minutes. Print from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

Landscape for Fire (1972) by Anthony McCall

For Landscape for Fire, Anthony McCall and members of the British artist collaborative Exit followed McCall’s pre-determined score to torch containers of flammable material across a field. McCall describes it: “Over a three-year period, I did a number of these sculptural performances in landscape. Fire was the medium. The performances were based on a square grid defined by 36 small fires (6 x 6). The pieces, which usually took place at dusk, had a systematic, slowly changing structure.” The work brought the grid—a conceptual focus for many artists in the 1970s and after—into a natural landscape, merging it with the vagaries of outdoor space and fire. (Storm King Art Center)

Ray Gun Virus (1966) by Paul Sharits

The projector is an audio-visual pistol. The retinal screen is a target. Goal: the temporary assassination of the viewer’s normative consciousness. (Paul Sharits)

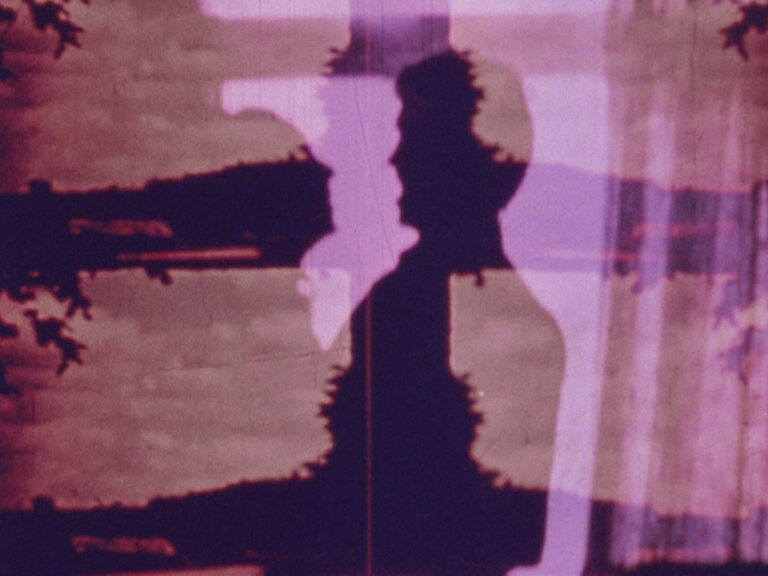

Plumb Line (1972) by Carolee Schneemann

The dissolution of a relationship unravels through visual and aural equivalences. The film splits and recomposes actions of the lovers in a streaming montage of disruptive permutations: 8mm is printed as 16mm, moving images freeze, frames recur and dissolve until the film bursts into flames, consuming its own substance. (Carolee Schneemann Foundation)

Nostalgia (Hapax Legomena I) (1971) by Hollis Frampton

In Nostalgia the time it takes for a photograph to burn (and thus confirm its two-dimensionality) becomes the clock within the film, while Frampton plays the critic, asynchronously glossing, explicating, narrating, mythologizing his earlier art, and his earlier life, as he commits them both to the fire of a labyrinthine structure; for Borges too was one of his earlier masters, and he grins behind the facades of logic, mathematics and physical demonstration which are the formal metaphors for most of Frampton’s films. (P. Adams Sitney)