Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969) by Ken Jacobs

Tuesday, December 2, 2025, 7:30 pm

Remembering Ken Jacobs

Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son

Presented in association with Gray Area

Admission: $15 General / $12 Cinematheque Members and Members of Gray Area

Event tickets here

Download Program Notes

Form is only interesting to the extent that it verges on formlessness, to the extent that it challenges incoherence.

— Ken Jacobs

“And whatever its source in Jacobs’ libidinal economy, his commitment to failure—his refusal of mastery, perfection, and control, and his insistence on rejectamenta, breakdown and ephemerality—reflects an objective political condition, the obsessive recurrence to which marks him as one of the most important artists of the period of late capitalism.”

— David James

Eisenstein said the power of film was to be found between shots. Peter Kubelka seeks it between film frames. I want to get between the eyes, contest the separate halves of the brain. A whole new play of appearances is possible here.

— Ken Jacobs

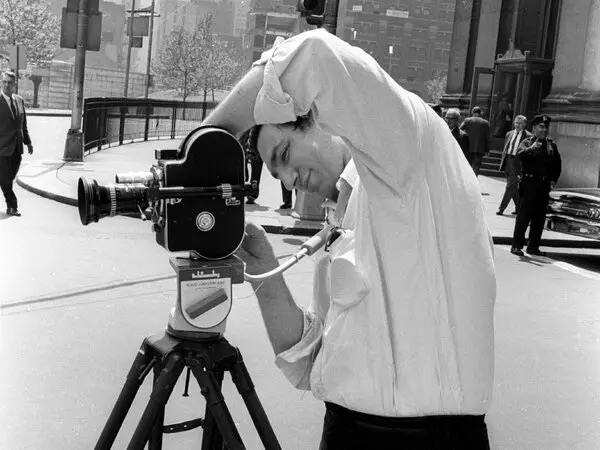

With the October 5 passing of filmmaker Ken Jacobs (b. Williamsburg, Brooklyn; 1933), the film world lost one of its most original, iconoclastic, endlessly engaged and most restlessly explorative filmmakers, a filmmaker whose body of work eschewed classical elegance in favor of a concrete cinema of material engagement and social provocation. Although deeply influenced by the push-and-pull aesthetics of abstract painting, Jacobs began working with film in 1955, and, active until just weeks before his death, created a vast body of work which explored the mechanics of the cinematic apparatus, the profundities and paradoxes of perception and the politics of representation inherent in the media of in twentieth and twenty-first century capitalism. Following early works based on arte povera aesthetics drawn from impoverished New York existence (including ‘50s-era entropic camp classics made in collaboration with legendary performance artist Jack Smith), Jacobs produced an overwhelming body of work—including 16mm films; found footage works; digital video essays and abstractions; and scintillating, flicker-based, multi-projector 3-D performances—elaborating the interfaces of illusionism, cinematic materiality and organic eye/brain perceptual mechanics, an ecstatic, bracing and challenging body of work, which, while rooted solidly in roilingly squalorous reality offered glimpses of the profound (and decidedly non-spiritual) ecstasies of experience.

Our tribute to Ken Jacobs will include Window (1964), an entirely in-camera “cinematic action-painting”; Mountaineer Spinning (2004), stroboscopic and hallucinatory digital video translation of one of Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern performances and Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969), Jacobs’ obsessive deconstruction of an early cinema amusement, an exhaustive work which extracts a visually cacophonous catalog of narrative and non-narrative cinematic potential.

I want to work with experience all the time.

— Ken Jacobs

SCREENING:

Window (1964) by Ken Jacobs; 16mm, color, silent, 12 minutes. Print from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative. Mountaineer Spinning (2004) by Ken Jacobs; digital video, b&w, sound, 26 minutes. Exhibition file from Electronic Arts Intermix. Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969) by Ken Jacobs; 16m, b&w, silent, 115 minutes. Print from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

TRT: 141 minutes

Window (1964)

Ken visited Willard [Maas] and Marie [Menken] in their penthouse, and was chewed out by Willard for not having a beginning, middle and end to his films. Willard’s criticisms didn’t upset Ken as they might have earlier in his life; he had begun to feel that there was a general comprehension of his work. He saw that new forms were arising from many people who also had had bitterly insufficient childhoods. The roots of it can be clearly seen in his 1964 film Window. There is nothing to this film whatever if one does not understand what it is to be stuck with your window that looks out on the meanest, cruelest scene—the shabbiest of walls. Your window looks out on the scrubbiest brick and god-damneddest dirty surroundings conceivable. It represents the whole emotional suffering of your life. Your parents are that window to the world, your school is that wall and your spirit has had to live through it. Here is a man up against that window and those walls, making his entire articulation out of this desperation. Window could be thrown out of focus and its very rhythms alone would articulate a meaning. People saw that meaning, the feeling, in Window, and many appreciated it. (Stan Brakhage: Film at Wit’s End)

Mountaineer Spinning (2004)

We seem to be seeing a rustic landscape, perhaps. Everything here seems to be a perhaps, including allusions to Beauty and the Beast and [whether or not] we are or are not seeing in 3-D. As in real life, everything is in constant motion (although unlike life not necessarily going anywhere, more like suspended in motion), achieving or foregoing distinction as specific entities. Rick Reed does the Mendelsohn and here too lines are blurred between life-recording and astral electrons at play. (Ken Jacobs)

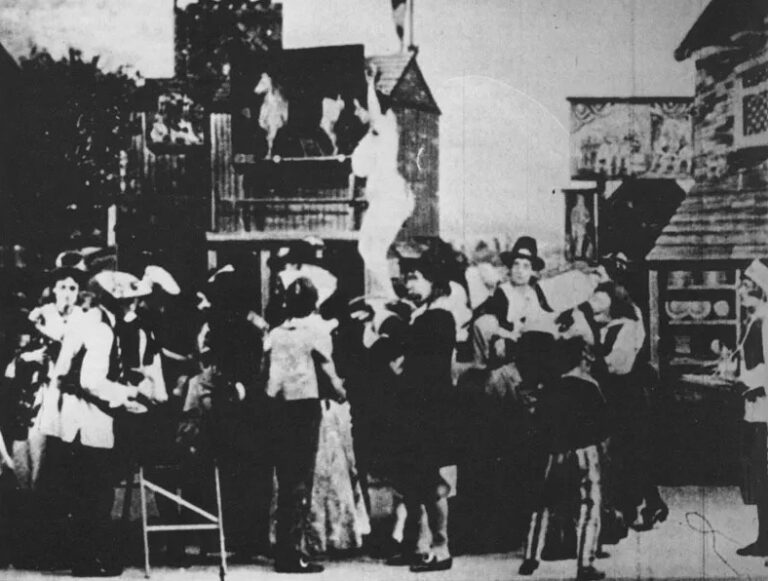

Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969)

Original 1905 film shot and probably directed by G.W. “Billy” Bitzer, rescued via a paper print filed for copyright purposes with the Library of Congress. It is most reverently examined here, absolutely loved, with a new movie, almost as a side effect, coming into being. “Ghosts!” Cine recordings of the vivacious doings of persons long dead. The preservation of their memory ceases at the edges of the frame (a 1905) hand happened to stick into the frame…it’s preserved, recorded in a spray of emulsion grains). One face passes “behind” another on the two dimensional screen. The staging and cutting is pre-Griffith. Seven infinitely complex cine tapestries comprise the original film, and the style is not primitive, not uncinematic but the cleanest, inspired indication of a path of cinematic development whose value has only recently been discovered. My camera closes in, only to better ascertain the infinite richness (playing with fate, taking advantage of the loop character of all movies, recalling with variations some visual complexes again and again for particular savouring), searching out incongruities in the story-telling (a person, confused suddenly looks out of an actors face), delighting in the whole bizarre human phenomena of story-telling itself and this within the fantasy of reading any bygone time out of the visual crudities of film: dream within a dream! And then I wanted to show the actual present of the film, just begin to indicate its energy. I wanted to “bring to the surface” that multi-rhythmic collision-contesting of dark and light two-dimensional force-areas struggling edge to edge for identity of shape… to get into the amoebic grain pattern itself—a chemical dispersion pattern unique to each frame … stirred to life by a successive 16–24 pattering on our retinas, the teaming energies elicited (the grains! the grains!) then collaborating, unknowingly and ironically to form the always-poignant-because-always-past illusion. (Ken Jacobs/LUX)

There’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deeper look, toy with it, take it into a new light with inventive and expressive projection. Freud would suggest doing so as a way to look into our minds. (Ken Jacobs)

There’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deeper look, toy with it, take it into a new light with inventive and expressive projection. Freud would suggest doing so as a way to look into our minds. (Ken Jacobs)