On the Way Home 關於回家的路上 (1989) by Goang-Ming YUAN

Thursday, June 26, 2025, 7:30 pm

Then<·>Now

Taiwan Experimental Film and Video Art

Curated and Presented by Cherlyn Hsing-Hsin Liu

Admission: $15 General / $12 Cinematheque Members

Program presented in association with the Center for Asian American Media and the Asian Art Museum

Event tickets here

Download Program Notes

San Francisco Cinematheque is proud to present Then<·>Now: Taiwan Experimental Film and Video Art, a single-evening distillation of a three-program series presented at Los Angeles Filmforum March 2025. This program includes six works created 1989–2018, each complex reflections of Taiwanese artists’ relationship with international avant-garde culture and the nation’s own fraught and contested political history.

The series Then<·>Now: Taiwan Experimental Film and Video Art is curated by Cherlyn Hsing-Hsin Liu and is presented in association with the Center for Asian American Media.

SCREENING:

On the Way Home 關於回家的路上 (1989) by Goang-Ming YUAN; video, color, sound, 14 minutes.

The Spirit Keepers of Makuta’ay (2018) by Yen-Chao LIN; Super-8mm screened as digital video; color, sound, 11 minutes.

Van Gogh’s Ear 梵谷的耳朵 (1995) by Mi-Sen WU; 16mm screened as digital video, color, sound, 20 minutes.

Cotton Sugar (2009) by Tsen-Chu HSU; 16mm screened as digital video, color, silent, 4 minutes.

Yi-Ren (the person of whom I think) 伊人 (2015) by Tzu-An WU; digital video, color, sound, 14 minutes.

Noah, Noah 諾亞諾亞 (2003) by Chun-Hui WU; 16mm, color, sound, 20 minutes.

Then<·>Now: Taiwan Experimental Film and Video Art: Around 1960, Taiwanese artists were inspired by the exchange of avant-garde cultures from around the world and began to develop a concept of modern experimental art. Many artworks created at that time had a profound impact on Taiwan’s subsequent culture. The achievements in modern experimental poetry, experimental theater, surrealism and documentary photography are still important today, laying a solid foundation for Taiwanese avant-garde art.

We must not forget Taiwan’s complicated history and geographical location. After World War II, in 1945, Japan ended its fifty-year colonial rule over Taiwan. In 1949, the Chinese Civil War ended and Chiang Kai-shek took his troops to Taiwan and began the Kuomintang’s (KMT) political rule. After 1990, Taiwan began the process of democratization and has been implementing the rotation of the ruling party up to the present day. In this wave of political changes, the most neglected are the indigenous people of Taiwan and many stories about them have been left behind in the torrent of history.

Geographically located between China and Japan, many Taiwanese people chose to study in the West or encouraged their children to do so during the Taiwan Economic Miracle (1960s–1980s). After returning to Taiwan from abroad, this generation of students injected many new elements into Taiwan’s modern art and academic research, especially in the areas of literature, painting, film, dance and music. Experimental filmmaking in Taiwan started around 1960 as many artists connected with traditions of Dada and Surrealism, opening a ray of hope for young students who had long been oppressed byTaiwan’s political situation. Filled with disgust for war, these artists also hoped to rebel against traditional Chinese and Japanese aesthetics, embracing modern art practices from across the world. With the continuous breakthroughs in photographic technology, coupled with the accessibility of equipment, many young Taiwanese artists have also joined the ranks of experimental filmmakers in recent years.

During the period of Taiwanese “White Terror”—a period of intense political repression of Taiwanese citizens 1949–1991 by the KMT—Taiwanese people were forced to speak Chinese, following fifty years of enforced Japanese under the colonial period. In response to this, Taiwanese art of the time involved extensive use of allusion, symbolism, metaphor and metonymy as artists explored issues of marginality, obscurity and multiple identities experienced at the time. More contemporary work, including works in this program, reflect a much less restrictive linguistic context, one which interweaves Taiwanese, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and English and gives rise to a kind of decolonization, defamiliarization and entanglement. As with many places around the world, experimental films have always been in a relatively marginal position. Compared with narrative films and traditional documentaries, experimental films are often ignored or misunderstood. Therefore, artists working in these genres have few resources in Taiwan. During my curatorial research, I found that many early works of experimental film in Taiwan have been lost or have not been properly preserved and thereby have only been rarely screened and have not received government support or been the subject of academic research.

This ongoing research project, Then<·>Now: Taiwan Experimental Film and Video Art, serves as a prelude to further exploration and research. Its purpose is to allow these marginal experimental films to continue to be screened, viewed, and discussed, so that they can have the opportunity to circulate and be properly preserved. (Cherlyn Hsing-Hsin Liu)

Gratitude in support of this series and program is extended to Adam Hyman, Michael Pisaro-Liu and the Center for Asian American Media.

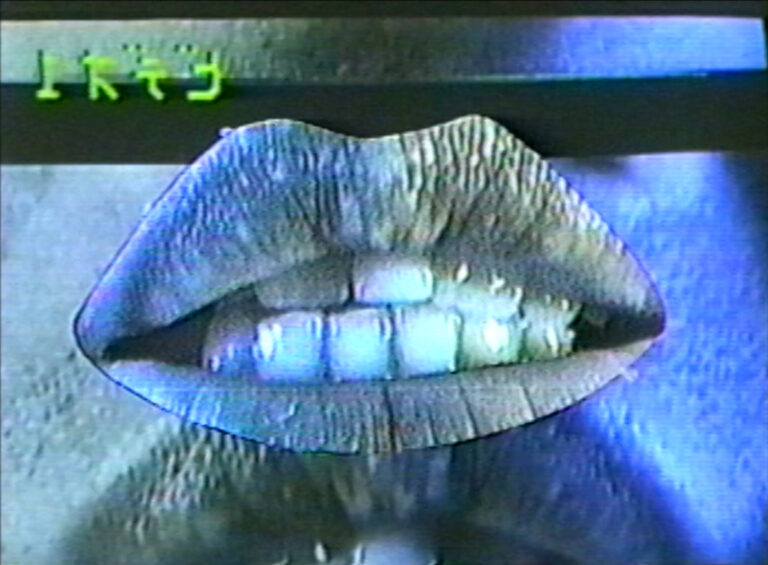

On the Way Home 關於回家的路上 (1989) by Goang-Ming YUAN

A man walking home in the rain holding an umbrella. Daily household activities. The bathtub and washbasin are filled with water and continue to overflow. Men’s round glasses become two hollows flashing with TV noise. The close-up mouth is interspersed with special effects, pornographic films and cannonball shooting scenes. Then there is a speech-like scene. You can’t hear the full content but vaguely hear some repeated words: thank you, I will say it again, every minute, every second, every thought, uneasiness and fear. The film ends with the song “Just Walking in the Rain” (1956). (Goang-Ming Yuan)

Yuan Goang-Ming: Everyday War is on view at the Asian Art Museum through Aug 4, 2025.

The Spirit Keepers of Makuta’ay (2018) by Yen-Chao LIN

Shot on location in the traditional Amis territory, The Spirit Keepers of Makuta’ay travels through villages on the east coast of Taiwan, where nature, colonization and population migration merge to create a unique spiritual landscape. The hand-processed Super-8 unravels mixed faith expressions from Daoist ritual possession to Presbyterian funeral, from personal prayers to collective resistance, all the while attempting to trace the memories of past Amis sorcerers. (Yen-Chao Lin)

Van Gogh’s Ear 梵谷的耳朵 (1995) by Mi-Sen WU

The film is constructed in three “chapters.” The two brief introductory sections lead to the final segment on Allen Ginsberg. In the film the filmmaker attempts to humanize the legend of Allen Ginsberg. Passages revealing the poet engaged in the common act of taking a taxi and addressing a class student present a mortal image of the poet/philosopher. These moments juxtaposed with more familiar poetic vision creates a unique portrait of this legendary figure. David Schwartz, the curator of the American Museum of the Moving Image, has described the film as a visual smorgasbord combining editing and content to perfection with a striking and energetic with a rich spiritual vision sewing together three different sections with a stylish non-narrative form. In Wu’s work he attempts to expose the contradictions between life and art by disturbing the boundaries of fiction and reality. Mi-Sen Wu hopes that his film will inspire audience sensitivity to these contradictions. (Mi-Sen Wu)

Cotton Sugar (2009) by Tsen-Chu HSU

By working with film as a medium, I have discovered a way to implement my interest in weaving both concepts and materials; integrating different elements into one work. In this piece, I covered the film with cotton and tinted it with dyes. The textures of cotton adhered to the film create a new layer; the original emulsion and the added textures coexist, cover and uncover each other at the same time. The differentials of color tones, the positive and negative footage and the alternations of abstract and recognizable imagery introduce a dialogue about the possibilities of opposite characters. This is hand-processed film. (Tsen-Chu Hsu)

Yi-Ren (the person of whom I think) 伊人 (2015) by Tzu-An WU

Yi-Ren (can be vaguely translated to “the person of whom I think”) is a collaged love letter from various sources. Such as my Super-8 diaries, karaoke videos and found footage from Kang-Chien Chiu’s (1940–2013) films and poems. It is also an act of homage and a queer reading of Chiu. Reassemble, manipulate the materials and melt the ready-made and the personal into one. Or, maybe the personal emotions and experiences are all borrowed from someone and somewhere… As the line “my moans have a bit of Hollywood in them” suggests, our emotions would not exist without acting, or movies we have seen. (Tzu-An Wu)

Noah, Noah 諾亞諾亞 (2003) by Chun-Hui WU

A lover in the past disclosed a life eroded by cancer in an email. May 2003, plague and death expand. Noah sails once again in a journey without an end. Following Noah’s voyage, searching for the origin of memory and the infinite desire. Collecting images. The image-memory in the home movies made for the past six years. The act of film-collecting has gradually become a desire to fetishize. Image-fetish, film-fetish and memory-fetish. Through the reproductive relation, such desire is transformed into a filmic act and experience. Fragments of imaginary landscape have been cut into traces of memory. Images split, connect and jump over, roaring over like the imagery movement in the brain, rising in the distance just to be vanishing once again. The images of arrival and departure repeat themselves in a loop. The desired objects slowly emerge from afar. The troop of men advances face to face and the glamorous queens move out hand in hand. A parade of single frames move ahead and the images flee. It’s about a journey and a distance. A distance from one point to another. Trains departing, highways, navigating by water and air. A distance of filming. A distance from one image to another film roll, from one frame to another perforation. A distance from the real to the memory. It’s about distance and human relations. A relation between friends; a relation between lovers; a relation between bodies. The more intimate and close it gets, the more vague it becomes. Human body will eventually become an abstract landscape, in which the distance and relations between the perceived and perceiving will be manifest. (Chun-Hui Wu)